Life On the Severed Floor

Reflections and Insights on Life in the Corporate World

The alarm blared. My eyes snapped open into a half-conscious panic. Groggy. It was 7am. I hurried through a shower to get out the door; to get to the car so that my dad could drive me to the train station. From one station to the next, I droned to the office to do lifeless work, and after a day drudging through spreadsheets, emails and documents, I took the little time I had left to find the vocation that would one day maybe imbue meaning into my work.

This was my introduction to the Severed Floor.

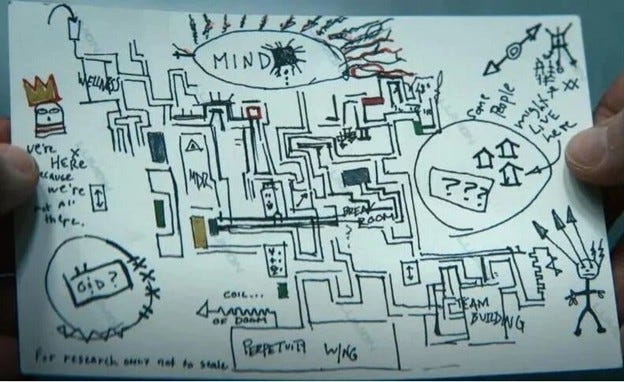

The elevator in the Apple TV series, Severance, activates the chip in a severed employee’s brain, turning off their “outie’s” consciousness, as if they snapped asleep, giving birth to an “innie,” an employee of Lumon—the company running the severance program.

Stepping off the train activated innie-Dom (Dom S). Fortunately, I was conscious of the change in personality. Dom S still held my belief: the corporate job1 wouldn’t allow full expression of self. A terrifying notion I carried with me to the workplace.

One might think that’s overstated, but the shaping nature of the corporation remains unarticulated in full. I was and remain hyper-adamant about my information and social diet. These things mold and shape us every day, reinforcing unconscious patterns: good, bad, or benign. A corporate job tends to have these shaping features. Especially given the inculcating nature of a job’s culture, it is challenging to catch all that it reinforces, regardless of how adamant one is.

My psyche was in Severance’s grip from the moment it premiered. When that happens, I know the story contains necessary information I must understand. When a culture is gripped by a story, there’s something profoundly necessary we must understand.

Severance is a perfect story for our time.

It captures and explores ideas and themes permeating our increasingly absurd work paradigm, and the absurd effect it has on its workers.

Because I recently left the corporate world in pursuit of an alternative path, I wanted to reflect on the 6 years I spent in corporate life.

So that I don’t risk recapitulating another trite ‘end of the corporate job’ post that shouts, “9-5 Bad! Pretend work! Dull!” I will instead start by making a formidable case for the corporate job and making it as strong as possible. Only then will I whisper the case against it. I will then think about how to manage the innie and outie as one (with some wisdom from Severance), and finally, what the pathway forward looks like.

I’ll do all of it while referencing our cast from the most benevolent corporation known to the non-fiction and fiction world alike, our pioneering friends in the biotechnology world…

Lumon Industries.

Let’s step into the elevator together, shall we?

!Spoiler alert through end of season 2!

Macrodata Refinement

“If you could be any kind of door, what would it be?”

In Severance, season 2, episode 2, Dylan G’s outie needs to shop around for a new job after he’s notified that Lumon is terminating his employment. With two young kids to provide for, it’s made clear that he needs the money and benefits he just lost.

Dylan walks into a door factory for an interview with the manager of Great Doors; he’s asked about why he would be a good fit… at a door factory. In the first episode of the Severance podcast, the writer of the show talks about how the last job he had before selling his script was at a door factory, which I think makes this strong piece of commentary even more grounding, being that it was the launchpad for the show’s inspiration.

This 3-minute clip is Dylan’s interview. Worth every second.

This alludes to the foremost reason to work a 9-5: while the work might be meaningless, it provides money to afford meaning outside of the job.

One way I like to define money is: your skills and effort made tangible and transmittable through time and space. In that context, jobs that may be meaningless allow you to trade your time and skills into something that can be leveraged for the things that do mean something to you—in Dylan G’s case, his family.

It’s one of our time’s biggest struggles: the tug between paying the mortgage and the pursuit of meaning.

Beyond money, it provides stability.

Jobs ground you into the world. When you’re riddled with confusion about your life, unsure of where to go or who to be—and no wonder, with all the muddled information spread through social media, friends, family, community, and society—a job provides you with a grounding sense of you. It fills the persona’s container, which can be stabilizing.

Given all the variables and complexity of humans, it’s no wonder most people don’t know what they want by the time they’re 18. So, how do you proceed? You pick something that seems close to what you think you want, something that’s most interesting to you at that given time and give it a go.

Some people nail it with the first thing they point at. But there’s a good chance it will change, and maybe drastically (i.e., Accounting -> CPA -> Technology audits -> security risk management -> writing fiction and this newsletter). Change or not, it grounds you into a productive channel of society for yourself and others.

The money and stability hurdles are enough to keep people occupied for a lifetime. If conquered, the search for meaning smacks people in the face (something like a midlife crisis).

Another reason is that some people simply find meaning directly in the work they do for a corporation! How many fall in this category? A Pew Research survey cited that there was an overall median of 25% of people who mention work as a source of meaning. Though, this varied by country (17% in the US), and there was quite a stark difference in the level of reported meaning based on the income level.2 This includes all jobs, so those who are outside of the 9-5 paradigm could also fall within that 25%. So how many truly find meaning in their corporate jobs? My guess is as good as yours. The cynic says 1%, the optimist, 20%. Or maybe the optimist says 1%, the cynic, 20%…

Here’s an interesting thought experiment: If everyone had all the money they needed and all the resources they could ever ask for, what percentage of people would continue working their current job rather than find a new vocation?

Another reason often overlooked is that there is a large portion of society that will just do whatever the average thing to do is—by definition. If the work paradigm in 2100 is one where 90% of people are tilling gardens (uh-oh, post-apocalypse?), then most people will till gardens… in the spaceship vegetation room (nah, it’s actually great). It’s what’s available. It’s what 90% of people do. Therefore, if given the choice 9/10 times, you’ll till more than you’ve tilled before.

Navigating an individual path is uncertain and can be destabilizing. If one prefers safety and doesn’t anticipate holding any kind of meaningful vocation, then on the normal path they go.

The modern version of that thing is the corporate job.

Another unapparent benefit is that working at a company can afford someone individual development through skill and wisdom transfer.

Companies offer responsibility; in responsibility, there is something to be taken, learned, processed, and performed. When someone gets effective at using the tools and skills required for said responsibility, they’re given more opportunities to continue that development.

It was through my time in the corporate world that I was pushed to develop my productivity system, to learn best ways of processing information and weighing decisions, managing meetings and interviews, planning projects, allocating and prioritizing work. It was through the responsibility of presenting a quarterly meeting for executives that I was forced to strengthen my public speaking skills.

I think that while all these things can be obtained outside of the corporate paradigm, they are an obvious place where this gold is found. So, if you’re the type (like me) who was hedging while trying to get out, then this is an added benefit.

If four reasons weren’t enough, I think there’s one that I will not elaborate on much. It’s a place where connection is formed. Friends are made and connections with clients/patients are formed. Some businesses manage a family-like relationship and for some that surpasses everything. It’s your family away from family and that’s meaning enough to do whatever banal tasks may fill a day!

So, we have:

1. Money

2. Stability

3. Normalcy

4. Skill-mining

5. Connection-building

For me, all these benefits don’t outweigh the proverbial soul-suck. When I managed a team of people, there was marginally more meaning, but it still felt far from the thing I should be doing.

That brings me to what I feared the most with the corporate job. While I don’t have as many reasons for leaving a corporate job, the core reason to flee is stronger and surmounts all the reasons to stay.

Constituent to the Whole

“I think it’s time to go back to the basics, Seth. To remember these severed workers’ greater purpose… and to treat them as what they really are.”

We tend to see AI as the first emergent intelligence alongside humans, but what about corporations?

Corporations seem to behave as an intelligence of their own. They have their own guiding star (vision), a statement of how to get there (mission), pathways to achieve that mission (strategy), the morals to drive toward the strategy (values), and a hierarchy of intelligence (both biological and digital) that each serve a specific purpose to achieve the organization’s goals.

So, what happens when an individual’s values are misaligned with the direction of the team they work within, or the company they inhabit?

In Severance, Seth Milchik is reminded by his superior to “treat them as what they really are.” To treat the innies not as people, but as slaves to the company’s greater purpose. Of course, this is the concept I’m alluding to taken to its extreme, but it’s ultimately what the corporation has its interest in—preserving itself—whether that’s at the cost of the individuals within it or not.

In competent, meritocratic, and benevolent hierarchies, individuals are empowered to speak up. Their ideas are given a chance to win in the battlefield of ideas, where truth emerges as the winner.

This is the ethos a good manager maintains with their constituents.

In practice, this is often disincentivized.

Sticking your neck out makes you vulnerable, which can harm you and the safety you derive from the job. It’s uncomfortable to deviate from the norm, and because of that, when you deviate, others can respond harshly so that you step back in line.

As hard as it may be in the short term, I’ve always seen it as worthwhile. Staying silent and complicit is a decision just as much as speaking out is.

The challenge of speaking out is easy enough to talk yourself out of, especially if you argue with yourself knowing that you:

1. Need the money

2. Don’t want to step into the chaos of unknowing

3. Don’t care enough about what the team or company does

It makes it even easier to float along with the misalignment between employee and employer. I still argue that it’s worth speaking one’s mind, at the very least to retain a sense of self at work (not to be done recklessly).

What lies at a deeper level of analysis is the feeling of a soul-sucking job. It’s a common term used to describe a job that, maybe on the surface, is okay, but agonizes because it feels like it diminishes your soul.

What is going on there, exactly?

Again, Dylan G is the perfect example.

His outie is a complete shell of himself. Like a distant remnant of someone who once cared but is now drained. His outie and wife always seem exhausted and beaten down.

Then, he walks into the Great Doors interview knowing he needs the benefits. Look, I don’t know if Dylan is a door fanatic, but when prompted with the question: “If you could be any door, which would it be?” and you need to conjure excitement to appease a potential employer, it takes a piece of soul. It’s unfortunately and painstakingly necessary.

One can even infer the reason he entered the Severance program in the first place was to escape the agony of the soul-suck while still getting the money and benefits he needs.3

The soul-suck, for me, felt like I was being pulled from another purpose I should be serving. Like there was a call I needed to answer but couldn’t. Like there was a higher intelligence trying to pull me in a direction, and I was going the opposite way. Every time the clock ticked, and I pushed through my tasks with sheer grit, it felt like there was something far more important for me to be doing.

I can recall standing at my work laptop to start my work-from-home day, and feeling like there was a literal tug toward my personal desktop where I served the vocation.

It is that which, to me, is the greatest loss, and ultimately pulled me from the corporate world. There are many other reasons that one would leave, though I tend to think they run downstream of this. The ultimate loss is the loss of self, and the conclusion I came to is that if it means loss of self or loss of job, I’d choose the latter (again, not to be done in haste).

The greatest hazard of all, losing one’s self, can occur very quietly in the world, as if it were nothing at all. No other loss can occur so quietly; any other loss—an arm, a leg, five dollars, a wife, etc.—is sure to be noticed.

~ Søren Kierkegaard

But, like I said, the innie develops a life, a personality, and a given skill set, so how does one reconcile that with their true character, and who they really are and want to be?

Severance, again, has an answer.

Reintegration

Mark S undergoes a process known as reintegration. The process aims to reintegrate your innie and outie into one where memories, thoughts, and personality merge. Two fragmented minds become whole again.

The answer Severance provides is brilliant (the entire show is genius). It begs the question: how can someone reintegrate themselves?

For me, the process included foraging for a sense of meaningful expression, and from there I would search for the potential to generate income to support my family. All the while, Dom S. was bringing in the money and saving it so that when the outie found the vocation, he’d be ready to leap.

I always had a strong inkling that I didn’t want the corporate life. I wanted a self-sufficient path. It took me many attempts and failures to finally find what that thing was. That’s when I dove out and gave full rein to the outie, utilizing the innie’s skills along the way, and reintegrating.

Though it’s not quite drilling into your brain and being unconscious for days on end with nosebleeds and an array of cognitive symptoms, it’s difficult and I see why people don’t make the jump. I made cringe, embarrassing, and effortful-but-not-well-received attempts to find what it was. The path does take a true moral effort.

If you can find a way to generate meaning in your white-collar or blue-collar job and that satisfies you, that’s wonderful. For me, I felt that a true expression of who I was needed full individual autonomy, down to the time things get done, up to the macro: the vision I have for my vocation and its products.

The reintegration process also involves leveraging those things that are worthwhile from the corporate world: the systems that sustain, modes of communication, running meetings and interviews, managing and leading projects (which is what being self-employed is, really), and shedding those that are parasitic: the fake laughs, the little lies that keep your check safe, the uninteresting and soul-crushing tasks, and the necessity to associate with people who play power and political games.

On the road to reintegration, one may look up and see the inevitability approaching.

A decision:

Stay or go?

See You at the Equator

I tend to think that this is a question everyone needs to grapple with full honesty for themselves. The decision to leave is a hard one. I knew from before I even stepped inside the corporate world that it wasn’t for me.

I tried to manage the hybrid approach for a solid 5 years, which ended with a conclusion that was impossible to ignore. A path where I wanted to produce a meaningful life unique to me required my own path detached from corporate work. I was able to compartmentalize work, but still, when one acts, speaks, and executes in a way dictated by a work culture, not by their own, there is—even if just a little—part of them outsourced to the company. Even though I was very clear with myself about the boundary of job versus vocation, a neurosis still emerged that required me to find the individual path.

That said, if one can manage a hybrid path and feels that there is no problem with it, that’s great.

For me, it wasn’t possible.

The execution on the decision was a hard one; I had many try-fail cycles, stuck in a loop where leaving was too hard.

When the time was right, I made my decision.

While it comes with its own challenges, I now finish my weekend excited to start the week and wake up every day excited to get to the things I feel I’m meant to do.

I hope that everyone has that experience in their life, however that looks for them.

See you at the Equator.

Dom

This post is brought to you by Lumon Industries…

Just kidding. They’d hate this.

Praise Kier.

Through the course of the piece, I use the words: corporate work, corporate world, corporate job, etc. The intention is to capture something approximating the definition of 9-5 knowledge work. If you fall into that category but don’t necessarily work in an office, I leave the definition of the corporate job up for interpretation. If you feel that it fits for you, then it applies.

It’s hard to say whether higher income work tends to be more meaningful or that those who report their work as meaningful actually fall into the first proposed bucket—they derive indirect meaning from what money affords them. I should also note that I’m skeptical about surveys in general, but it’s the best source of data we have as far as I can tell. Source

Dylan’s wife visits his innie and we get some insight into Dylan’s outie life. It’s made clear that he “never really found his thing,” and she later tells outie Dylan that the innie reminds her of how he used to be. It provides insight into his background which is something like: An ambitious go-getter enters the corporate world only to find it’s not at all what was expected but rides it out and drains life from themselves trying to make amends for that feeling from the day job.

> I was able to compartmentalize work, but still, when one acts, speaks, and executes in a way dictated by a work culture, not by their own, there is—even if just a little—part of them outsourced to the company. Even though I was very clear with myself about the boundary of job versus vocation, a neurosis still emerged that required me to find the individual path.

Man, so much of this resonated with my own experience. Even if you're laughing at the corporate nonsense, vision and mission and all the performativity, some part of you is surrendered to perpetuate it; it's like Havel's greengrocer:

"[T]hey must live within a lie. They need not accept the lie. It is enough for them to have accepted their life with it and in it. For by this very fact, individuals confirm the system, fulfill the system, make the system, are the system."